The Strategic Dimensions of Chinese Arms Exports to the Middle East

This article analyses the growing Chinese arms exports to the Middle East. What is China’s interest behind establishing a ‘soft’ military presence in the region, which is witnessing a receding American presence? The article examines the general characteristics of China’s arms trade and how it ties into its Middle East policy

Analysis

By Mihir Vikrant Kaulgud

The article analyses the growing Chinese arms exports to the Middle East. What is China’s interest behind establishing a ‘soft’ military presence in the region, which is witnessing a receding American presence? The article examines the general characteristics of China’s arms trade and how it ties into its Middle East policy. It also briefly investigates the case of arms exports to Saudi Arabia and Iran to understand the strategic contours of these exports. In conclusion, the article argues that growing Chinese arms exports to the Middle East are rooted in China's desire for greater energy security and that this trend shows signs of an emerging multipolar world configuration.

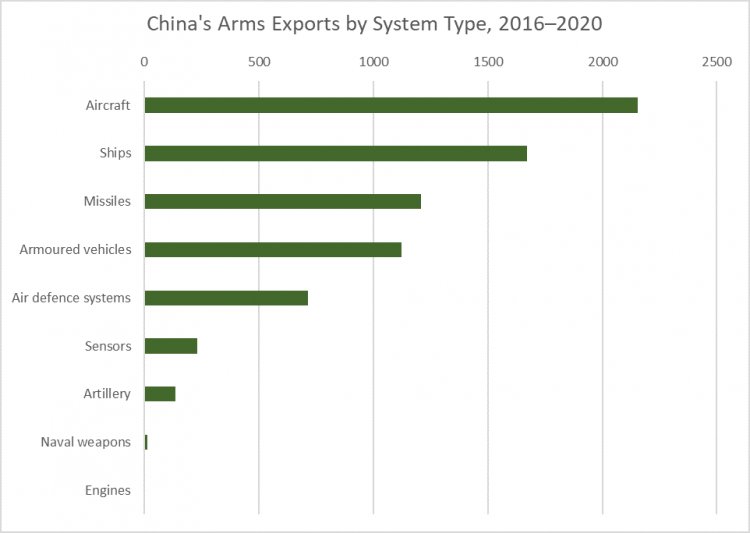

China’s emergence as a major player in the global arms market was driven by its motivation to advance the capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Consequently, it has reformed its defence industry and continuously increased its military expenditure to improve its defense equipment. China’s role in the arms market also reveals its awareness of the changing security environment where there will be increased strategic competition among global powers. Between 2012 and 2016, China’s share of global arms exports rose from 3.8 to 6.2 percent. Although in the 2016-2020 period it had dropped to 5.2 percent, China is still the world’s fifth-largest arms exporter. It has a very modest share compared to the US and Russia, but it is poised to enter new markets with new technologies. According to an analysis by the Centre for Naval Analyses, China has carved out an arms export “niche.” Figure 1 shows that China’s top arms exports include aircraft, ships, and missiles.

Figure 1. Source: Herlevi (2021), compiled using Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Arms Transfers Database. Figures are SIPRI Trend Indicator Values (TIVs), expressed in millions. CNA totaled TIV estimates for 2016 to 2020 based on SIPRI data accessed in April 2021.

The potential for Chinese ship exports is increasing, and according to a 2020 U.S Department for Defense Report, China is the top ship-producing nation in the world by tonnage. Another area where China is leading is armed drones (also called Unmanned Aerial Vehicles - UAVs). By 2018, China had exported heavy and armed UAVs to more than 10 countries worldwide. China has also agreed to jointly produce the Chinese Wing Loong II drones with the Pakistani Air Force. According to a 2013 SIPRI report, China is also a leading small arms and light weapons (SALW) exporter. It supplies to countries who cannot access these weapons from other suppliers - including states in the developing world and conflict-affected states. The report also notes that China is “among the least transparent” SALW exporters. Since small arms and light weapon transfers are difficult to track, more recent data is not available.

As countries look to modernise their military equipment on a budget, China’s drones and other advanced equipment are a big draw. China also offers flexible payment structures, which are attractive to developing nations. Moreover, countries looking to diversify their source of military equipment also find a good deal in Chinese arms. There have been concerns over the quality and longevity of China’s equipment, which might be connected to the drop in China’s share of global arms exports.

What are the characteristics of Chinese arms exports in the Middle East? China sells its weapons to any state that is willing to buy them - they harbour no qualms about what it sells and to whom. It appears that China is primarily interested in the commercial, and not political, gains that derive from arms exports. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that economic leverage is powerful, and so is the influence that comes with being an arms exporter, particularly to weak states. Much has been written on China’s propensity for “debt-trap diplomacy.” Arms exports are certainly an instrument of Chinese foreign policy, used for projecting power and creating spheres of influence in strategically important regions.

China’s broader Middle East strategy seems to support such objectives. It unveiled the Arab Policy Paper in 2016 and has made the Middle East a significant part of its Belt and Road Initiative. The Arab Policy Paper states that “we [China] will continue to support the development of national defence and military forces of Arab States to maintain peace and security of the region.” Hiim and Stenslie (2019) write that Beijing wants to become an influential player in the region, but in a much more pragmatic and restrained manner compared to the United States. They point out that China has tried to maintain good relations with all major countries. In doing so, it is flexible in its choice of partners - regardless of the regime and political differences. It has already shown a willingness to provide arms to conflict-affected states, for example, Libya during its civil war. China has avoided provoking the United States in this region, since the US security umbrella has “given China cover to expand its own relationships and networks in the region, allowing Beijing to present itself implicitly or explicitly as an alternative to US hegemony.” It has thus been called a “free rider” on US actions and interventions. China’s motivation for being an influential player in the region has thus primarily been economic, even though an aspect of this is military exports. Its attempts to build military bases in the UAE were foiled, although they could be interpreted as an indication of Beijing’s plans to create a network of naval bases to protect China’s commercial interests. The Chinese interest in exporting arms to the Middle East, especially in terms of economic leverage, can be partly explained by its desire for reliable suppliers of oil. China’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil is very high (47% of official imports in 2020). The unstable regional situation in the Middle East increases the risk of China's energy cooperation with countries in the region. This would explain its “win-win” approach in the Middle East, wherein China builds cooperative relations with oil-producing countries in the region. However, it must be noted that China’s military presence in the Middle East also acts as a strategic diversion, diverting the United States’ attention away from the Indo-Pacific. This comes precisely at a time when the US is diminishing its focus on the Middle East and refocusing on the Indo-Pacific.

In the Middle East, Chinese drones have been especially popular. Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have all received armed Chinese UAVs, including the Wing Loon and CH-4 drones. Thus, China may be aiding a UAV arms race in the Middle East. Moreover, the U.S implemented a restrictive export policy in selling armed drones to Arab states in the Middle East. China has exploited this reluctance or reticence to expand its own foothold in the region. For example, Jordan was turned down by the U.S from buying Predator XP drones. It then turned to China to buy CH-4B drones instead. Iraq has also followed a similar pattern, deploying Chinese drones against the Islamic State.

China’s relationship with Saudi Arabia is a prominent one in the region. A firm US ally, Saudi Arabia is one of the top importers of Chinese arms. The Saudis have procured Chinese DF-21 ballistic missiles and Wing Loong drones, with a deal to jointly-produce the CH drones in Saudi Arabia. In 2019, the two countries also conducted joint naval drills and in January 2022, the Chinese Minister of National Defence Wei Fenghe and Saudi Arabia's Deputy Defence Minister Khalid bin Salman hinted that the two countries’ militaries should improve practical cooperation. Therefore, the China-Saudi military relationship is on track to ever-closer ties. This relationship is – and will be – rooted in the fact that Saudi Arabia is currently the top supplier of oil to China.

In the commercial and strategic dimension, China’s relationship with Iran is worth exploring. They have signed a “Comprehensive Plan for Cooperation between Iran and China.” China has agreed to an investment of $400 billion in Iran over a 25 year period in return for lower Iranian petroleum export prices. China can thus expand its influence at a profit. The United Nations’ arms embargo on Iran expired in 2020, and it was not renewed. China has exported arms to Iran since the 1980s until the embargo was imposed. Iran was one of the first buyers of Chinese arms exports. To date, China has sold the Silkworm and C-802 missiles, which are both anti-ship missiles, to Iran. Furthermore, Iranian ballistic missiles have been developed based on Chinese design; Chinese technicians also reportedly assisted with this development. With the expiry of the embargo, China is well-positioned to help modernise Iran’s military-industrial base. There is now a potential for Iran to acquire advanced fighter aircraft and battle tanks. It is a matter of speculation whether such cooperation will lead to joint military exercises and the development of Chinese military bases; however, it should not be discounted. China also imports oil from Iran and continues to do so despite US sanctions, preferring lower costs to the risk of defying the US. In December 2021, China officially disclosed Iranian oil imports for the first time in a year.

China’s arms exports to the Middle are a sign of the emerging multipolar strategic configuration. Saudi military acquisition from both the US and China is evidence that the U.S is unwilling or unable to enforce a hegemonic influence over its partners. Therefore, Saudi Arabia and other key US allies in the region like the UAE can play both sides of the table - remaining close to the US while cultivating relations with China. Moreover, countries like Iran, which have a more anti-Western leaning, are also aligning with China. While China does not appear to be “challenging the US-led security architecture” in the Middle East, it will inevitably change the balance of power in the region.

China's approach in the Middle East has shown hints of the ideal of the “peace through development” model, as an alternative to the imposition of liberal peace that the West attempted. Non-interference, state-led development, and unconditional aid are parts of this strategy. This is consistent with the primarily economic role China has taken in the region. But regional conflicts between states and threat from non-state actors mean that “Beijing will likely struggle to maintain its neutral narrative as Chinese interests in the volatile region grow.” China specifically needs to maintain its energy security interests, which can be expected to be a primary motive of China’s Middle East involvement. Due to China’s reliance on the Middle Eastern countries for oil, it will seek to secure the region in the wake of the U.S military presence being withdrawn and its reluctance to use force.

Increasing arms sales, and related technology transfers, display a shifting concern towards the security of the region. Even leaving aside the question of energy, this is largely inevitable, because, with Chinese-assisted infrastructure development and provision of services (via BRI for instance), China will also need to secure these investments. Arab states might also look to China as an alternative security partner - one with a different approach displayed by the American hegemony. In the near future, China might be expected to create new security arrangements in a practical manner and get more involved in regional politics. Since the basis of its security engagement so far has been arms exports, they can be a stepping stone to a wider security and military presence in the Middle East.

Disclaimer: This article is author’s individual scholastic contribution and does not necessarily reflect the organization’s viewpoint.